THE Thirroul district is said to have been cleared of scrub and timber by women convicts. This statement does not sound so fantastic when we read that Bungaribee, near Penrith, was built of bricks hauled in handcarts by women convicts from Sydney.

The camp was at or near the present site of Thirroul. The occupants were neither lovely nor refined, for the majority were born and bred in the slums of England, educated in the prisons and hulks, and finally, after some years of this intensive training, were professionally engaged in the Female Factories of New South Wales.

There was one exception to prove this rule of cultural deficiency. Elizabeth —- was cast in a gentler mould. She was neither snub-nosed or wide-mouthed, her hair was not wild and unkempt, nor did she enrich her conversation with many forceful and unmelodious oaths. She did not, indeed, engaged much in conversation at all, for she was quiet and retiring. Only her eyes, set in a dull stare of horror, showed the agony of her mind.

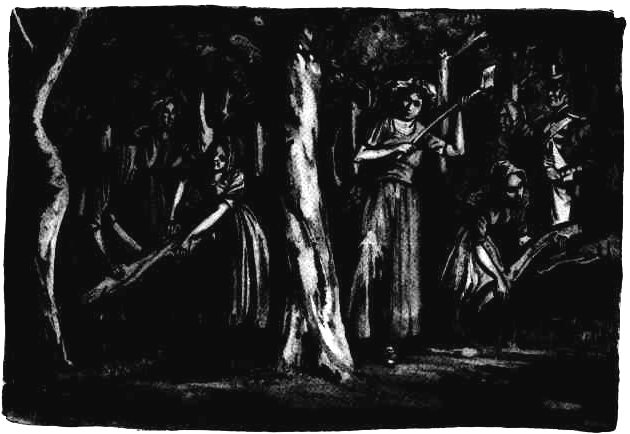

“The Thirroul District was said to have been cleared of scrub and timber by women convicts.” Photo: Sydney Mail, August 11 1937

What her crime was we do not know. It is as well to remember that, in England a century or more ago, the figure of Justice was not a beautiful woman, blindfolded and holding reliable scales ; she was wide-eyed and ugly, with a cruel mouth, and in either hand she carried a bludgeon. Thus, Elizabeth kept herself to herself, and her sisters in misfortune who were definitely more gregarious by nature, called her many rude names for being so “stuck-up” and aloof.

The camp was in an unhappy frame of mind. Food was disappearing. It was not appetizing food, but it was scarce and therefore highly valued. The ladies virtuously and indignantly accused each other of theft. Shreiking and shouting, they fought each other fiercely ; faces were scratched, hair was pulled, and there was a good deal of indiscriminate biting. The military were sent for and succeeded in restoring order. Greater care was taken in supervising the distribution of food, and for a time peace prevailed.

Elizabeth continued to keep herself aloof. When work was finished she wandered off for lonely walks by herself. Tongues began to wag. Various taunts were flung at her ; they were neither complimentary nor respectable. But Elizabeth took no notice.

Then one day, by the merest chance, a hag, prematurely old, leering at her toothlessly, said : “I suppose, dearie, you go a-visiting that young cove wot’s escaped from Camden. P’r’aps he’s yer fancy boy.”

“You foul beast!” cried Elizabeth, and hit her between the eyes.

The fight that the ladies had enjoyed previously was not to be compared with the battle which followed. Elizabeth’s blow was the spark which set fire to a bonfire of mob hysteria.. The fight became an “all-in” one. Fists flew and nails clawed, and a heaving mass of cursing, screaming women swayed to and fro across the erana. Once again the military arrived and restored peace.

Elizabeth continued her walks. She became even quieter and lonelier, and soon her companions noticed that she was rapidly becoming thinner. She had lost her apetite and would not touch the food she was given. She would sit staring at it listlessly. But, if her companions had watched her carefully enough, they would have seen her, with a swift movement, hide the rations in her blouse. Then she disappeared. The soldiers, who by this time had probably become rather sick of Elizabeth, searched far and wide, but with no success.

When Elizabeth escaped from Thirroul she followed the coast northwards for a few miles until she came to a spot where the cliffs came down sharply into the sea. She walked up to the edge of the cliff, searched for and found a winding secret path, which led down the face of it.

Painfully she crept down the path, clinging to bushes and pausing sometimes when a gust of wind tore at her – for she was very weak. She clambered over a boulder to find the mouth of a cave. A young man stood there gazing out to sea. He stared at her a moment, horrified at her appearance, then held out his arms to her with a cry of pity. Elizabeth ran to him, and he caught her as she fell.

“My darling,” she cried, “I’ve come to you – I couldn’t go on – I couldn’t go on -”

Some years later some fishermen were bobbing about in their little boat in front of that same cliff face.

“Blimey, Jim,” one of them said, “what’s that up there? Looks like a man!”

At the entrance of the cave they found the skeleton of a man, inside the cave the skeleton of a woman.

Thus ended this little epic.

– Then and Now, Historic Roads Round Sydney. By James Valentine. New Century Press 1939. The story also appeared serialised in the Sydney Mail during 1937.

Governor Macquarie described the Parramatta Female Factory as being almost completed in September 1820:

A Large Commodious handsome stone Built Barrack and Factory, three Stories high, with Wings of one Story each for the accommodation and residence of 300 Female Convicts, with all requisite Out-offices including Carding, Weaving and Loom Rooms, Work-Shops, Stores for Wool, Flax etc. etc.; Quarters for the Superintendant, and also a large Kitchen Garden for the use of the Female Convicts, and Bleaching Ground for Bleaching the Cloth and Linen Manufactured; the whole of the Buildings and said Grounds, consisting of about Four acres, being enclosed with a high Stone Wall and Moat or Wet Ditch.

© Copyright, Mick Roberts 2014

Would you like to make a small donation towards the running of the Looking Back and Bulli & Clifton Times websites? If you would like to support my work, you can leave a small tip here of $2, or several small tips, just increase the amount as you like. Your generous patronage of my work and research, however small it appears to you, will greatly help me with my continuing costs.

what was Elizabeth’s surname ? is she in the convict indents etc ?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unsure… Elizabeth’s surname was left-out of the story…. The posting is word for word from the book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

that’s one good love story

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Bulli & Clifton Times.

LikeLike