By MICK ROBERTS ©

THE terrible tragedy of a horrific mine disaster is remembered at the memorial in the yard of St Augustine’s Anglican Church, Bulli on March 23 every year – a day that changed the sleepy little mining village forever.

Mary Ann Jones was no novice when it came to mining disasters. She had seen it all before, although nothing on the scale that confronted her on that fateful Autumn day in 1887 when the Bulli Colliery exploded.

Mary became somewhat of a celebrity after she decided to take on the might of the region’s largest employer in the wake of the tragedy.

Her determined battle for compensation and outspoken criticism of the mine management won her respect and admiration from all quarters of the community after the explosion that rocked Bulli at 2.30pm.

Accidents in the dark depths of the coal pits were unfortunately part and parcel of mine work and Mary Jones had seen it all before. She had in the past helped bury mining accident victims in her motherland England by washing and shrouding bodies for burial. So it was only natural she offered her services after methane gas extinguished the lives of miners in her new home.

When confusion and grief took hold as mangled bodies began to surface from the pit portal, most women folk, who had lost husbands and sons, were in no fit state to prepare the victims for burial. Mine manager Alexander Ross asked Mary to receive the victims, wash, shroud, and prepare them for the grave, and, as she later revealed, to spare no expense. She accepted the commission and did as Ross requested, working with two other women for three days preparing the dead.

The Town & Country Journal reported on the horrific scene on March 26, 1887:

As the dead bodies are being brought out the scene is absolutely indescribable. The remains are in some cases burned to a cinder. The heads are smashed in, and the arms and legs broken ; and fearful gashes appear on the bodies. The clothes in many cases are burned to ashes. The hair is singed from the heads and faces, and the flesh roasted and shrivelled, on crooked, stiffened limbs. Identification is almost impossible, though it is attempted by examining the clothes of those brought to the mouth of the mine.

Mary received the 81 men and boys in the coal company’s work shed, located on the present corner of Hobart Street and the Princes Highway, as coffins were hastily knocked together on the road side. The corner would be a shocking reminder of the scene of despair, horror and devastation to those who witnessed the tragedy for years to come. Eighty men were employed to dig graves at St Augustine’s Anglican Church yard, where fathers and sons were buried side by side. Others were buried at Corrimal and Woonona. Under the impression from the mine manager that she was to be rewarded for her efforts over those frantic few days, Mary discovered that the Bulli Coal Company had no plan to pay her. She wrote to the company on July 1 1888 in an attempt to gain a payment:

“To the Directors of the Bulli Colliery Company – I have waited some time to see if you thought it necessary to recognise my services which I rendered in connection with the unfortunate men in the late explosion on March 23 1887. I think the least you could have done was to recognise my services. I have been connected with colliery accidents and deaths in England, and I may say that I always had my services acknowledged in a satisfactory manner. I mentioned the case to your manager, Mr A Ross. He said he spoke to you on the subject, but you gave him no reply, so I thought I would write to you myself. I wish for you to know how long I was among the dead. I was there from Wednesday afternoon till Friday night, also from Saturday morning until night.

– Yours respectfully, Mrs MA Jones.”

Controversy erupted when Ross rejected Mary’s claims of payment and denied he had used the words “spare no expense”, saying she did the duty out of kindness.

The events came to a head in April 1888 when Mary summoned the Bulli Colliery to the Sydney District Court in an endeavour to recover £20 and 5 shillings for “work done and services rendered” as a result of the Bulli disaster.

It was a case that immediately sparked intense interest and attracted great media attention.

Such a ghastly case had never before been heard in an Australian court.

Ross told the court that he may have made the remark “spare no expense” to have the bodies decently prepared for burial around the many people gathered around the pit mouth, but denied saying it directly to Mary.

The Honourable Judge Murray came to the conclusion that although both parties believed they were speaking the truth, Mary’s evidence was so positive and so consistent with common justice that the “verdict be awarded to the plaintiff”.

Mary Ann Jones was granted her £20 and 5 shillings for services, plus court costs.

The community are invited to the annual Bulli Mine Disaster service, hosted by the Black Diamond Heritage Centre, at St Augustine’s Anglican Church, Park Road, Bulli on March 23 where wreaths are laid at a monument near the last resting place of the victims. Check local guides for times.

© Copyright Mick Roberts 2014

Subscribe to the latest Looking Back stories

Would you like to make a small donation towards the running of the Looking Back and Bulli & Clifton Times websites? If you would like to support my work, you can visit my donation page where you can leave a small tip of $2, or several small tips; just increase the amount as you like. Your generous patronage of my work and research, however small it appears to you, will greatly help me with my continuing costs.

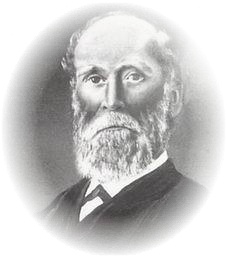

The article states the Mine Manager is Alexander Ross but the photo indicates the Mine Manager was Alexander Stewart. Is the photo actually Alexander Ross?

LikeLike

Yes, the image is of Bulli Mine Manager, Alexander Ross and NOT Alexander Stewart as stated. I have corrected the caption. Thanks for pointing this mistake out, Diana.

LikeLike

“The remains are in some cases burned to a cinder,” it was reported. “The heads are smashed in, the arms and legs broken, and fearful gashes appear on the bodies. The clothes in some cases are burned to ashes. The hair is singed from heads and faces and the flesh roasted and shrivelled.” do you know who stated this?

LikeLike

Local media at the time

LikeLike

Australian Town and Country Journal, March 26, 1887

LikeLike

Pingback: 2020 Bulli mine disaster memorial service | The Bulli & Clifton Times